The "Tour de France"

Journeying is characteristic of Compagnonnage. It means that the young worker is to sojourn in various towns where his association offers boarding and the help of elders to find employment for a few months. The idea is to provide the opportunity to gain a rich human and practical experience.

Journeying is characteristic of Compagnonnage. It means that the young worker is to sojourn in various towns where his association offers boarding and the help of elders to find employment for a few months. The idea is to provide the opportunity to gain a rich human and practical experience.

In each town where present-day compagnons have a local branch, you can find boarding quarters, classrooms, workshops and meeting halls, but before the mid 20th century the compagnons would lodge in inns. The brotherhood would draw up a contract with the landlord or lady by which they would have the use of a room for their assemblies and a secure place for their documents and treasure box. When small in number, two brotherhoods could have their local headquarters in the same inn. In return, the landlady would enjoy particular respect and be called « la Mère » and would have self-policing lodgers pledging not to leave any debt behind on their departure. You can still find ladies with that title nowadays, but their function is more of a bursar and adviser than an inn-keeper.

The geography of the Tour de France has changed significantly since 1950 and the compagnons’ associations (AOCD, UCDD and FCMB) are present in regions that were not frequented by the compagnons on their round journey before then, such as Brittany, Normandy, Picardy and the North, Alsace, Massif Central and also foreign countries: Germany, UK, Netherlands, Switzerland, etc. Young compagnons can find opportunities on all continents.

Specially significant in the past, the Tour de France also brings a broadening of the mind through immersion in different cultures and encounters with multiple personalities.

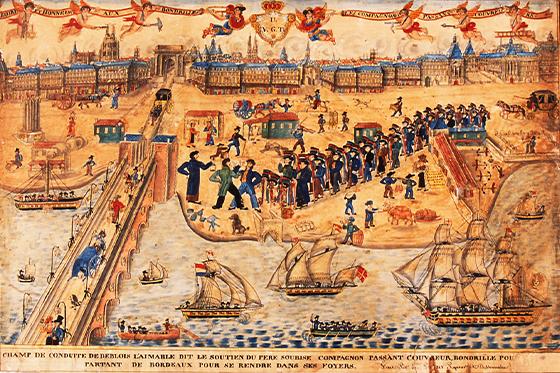

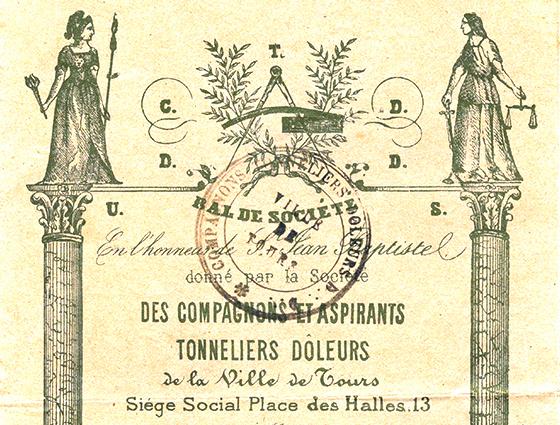

Till World War II, the Tour de France roughly followed the courses of the main rivers and the Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. A series of towns marked possible stopovers along this route. There, if his craft brotherhood had a ‘Mère’, the young journeyman could count on being accommodated and fed if he arrived penniless, and introduced to an employer by the compagnon assigned to this task. If no position was available, he would be given some money to keep him going to the next stop. There were ‘villes de Devoir’, where a copy of the code of rules was kept and where initiation of new compagnons could be organised, and ‘villes bâtardes’ that had no such authority. In the 19th century, cities that are known to have been ‘ville de Devoir’ for at least one craft brotherhood can thus be listed : Paris, Orléans, Chartres, Blois, Amboise, Tours, Azay-le-Rideau, le Mans, Poitiers, Saumur, Angers, Nantes, Niort, Fontenay-le-Comte, la Rochelle, Rochefort, Angoulême, Cognac, Limoges, Bordeaux, Agen, Toulouse, Villeneuve-sur-Lot, Tonneins, Montauban, Rodez, Montpellier, Sète, Narbonne, Béziers, Nîmes, Avignon, Marseille, Toulon, Vienne, Romans, Grenoble, Lyons, Saint-Étienne, Mâcon, Dijon, Beaune, Chalon-sur-Saône, Auxerre, Nevers, Troyes. As a consequence of industrialisation, some crafts got concentrated in areas where journeymen followed, attracted by employment opportunities: tawing and chamois-bleaching in Niort, Romans and Annonay; weaving in Lyons, Saint-Étienne, Tours, Elbeuf and Amiens; knife-making in Thiers and Nogent-en-Bassigny; rope-making in Rochefort, Angers and Toulon; cooperage in Cognac, Bordeaux, Sète, Mâcon, Beaune, Tours and other wine-producing regions.

Since the mid 20th century, some of these towns are no longer the scene of compagnonnage activity, but others have emerged: Brest, Caen, Le Havre, Strasbourg, Nancy, Lille, Arras, Anglet, Tarbes, Colomiers, etc.

The compagnons of olden days travelled on foot for economical reasons, but when they had sufficient means they used coaches and barges. Nowadays, they rely on cars, trains and even planes, but regularly you will see young journeymen honouring the tradition by walking a leg of their tour.

Contrary to a preconceived idea, there was no specified direction to journey on the Tour de France, the circumstances of the moment prompted the decision, yet one avoided retracing one’s steps as much as possible. Present-day young travellers go back home for the summer holidays and start in a different town in September. There is no fixed duration for the Tour de France: it generally takes between five and eight years, but there are known examples spreading over ten years!

The ‘mère’ of the compagnon farriers of Marseille in 1910

Ritualised leave-taking celebration for Blois l’Aimable, roofer compagnon, on his departure from Bordeaux circa 1825

Invitation card for a ball organised in 1908 by the coopers’ brotherhood of Tours.