Comparisons

The Compagnonnage is not just a vocational training association nor is it a Mutual Aid insurance nor a workers’ union. It is not a religion, nor a sect nor a secret society. Some of its traits are similar to freemasonry but there are important differences too.

The Compagnonnage can be defined by what it is not. It cannot be reduced to a vocational training organism nor to a Mutual Aid insurance nor a workers’ union although it covered all these functions in the past. It is not a religion because no creed in any form of deity is required and its members do not follow any cult except perfection in their work and a code of behaviour in society that may have originated in Christian values. It is even less of a sect: its aim is to favour an easy insertion of young people in society in general, not subtract them from it. Neither is it a secret society: its associations all have a legal status and some are registered on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of UNESCO. Its members do not hide that they are compagnons but it is against their ethics to advertise it for commercial ends.

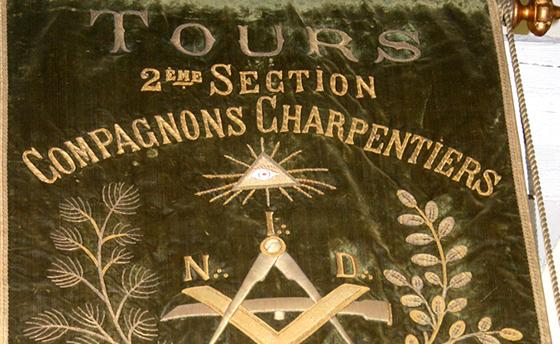

The Compagnonnage is sometimes mistaken for other movements, particularly freemasonry because they share the symbols of the interlaced compasses and set square. But beyond a few symbols and legendary references (notably to the building of Solomon’s temple) and the fact that they are both initiation societies, everything else makes them quite distinct. They have different geographic origins (England for the freemasonry, France for the compagnonnage) and separate histories (freemasonry appears in the early 18th century whereas the compagnonnage has a verified presence as early as the 15th century). Finally, the main difference rests on the plying of the craft of masonry: purely symbolic on the freemasonry side, fundamentally practised in the compagnonnage, among other crafts. Nevertheless, there obviously were elements borrowed by the latter from the former during the 19th century, but without any link resulting from the transfer and these two institutions have remained independent.

Other movements showed similarities with the Compagnonnage. The ‘Bons Cousins’ charcoal burners and the ‘Bons Compagnons’ splitters, the existence of which is verified as early as the 17th century, were initiation societies of foresters very similar to those of compagnons. During the 18th qnd 19th, because they admitted members from outside their craft, they mutated into mutual assistance gatherings and veered towards freemasonry or politics (Italian ‘Carbonari’, French ‘Charbonnerie’) before fading out in the regions where they were active (Burgundy, Franche-Comté).

There are also compagnonnages in the building crafts (carpenters, joiners, stonemasons, masons, roofers) in Germany and Scandinavian countries. Like their French counterparts, they journey and have secret reception rites. During their travelling period, they have to wear a typical corduroy suit and a black hat. The various brotherhoods mark their specificity through the colour of their neckties (black, blue or red) or a gold brooch.

In the course of the 19th century a number of associations of workers appeared, inspired by the compagnonnages and sharing with them moral values and high standards in work but rejecting their esoteric aspects. It was the case with the ‘Sociétaires boulangers’ or with the ‘Sociétaires potiers’ (potters) of Tours, or the more encompassing Union des Travailleurs du Tour de France. More defiantly and with tongue in cheek, there were the ‘Renards joyeux, libres et indépendants’ (Merry, free and independent foxes ─ ‘foxes’ being the word used by the carpenter compagnons for outsiders).

As early as the second half of the 18th century, it appears that some compagnons and freemasons had noticed similarities between their respective organisations. They both had initiation rites, secret passwords and means to identify themselves between members. But, if the frame was similar, the contents were different. Contrary to the belief, common among present-day compagnons as well as freemasons, the Compagnonnage is not an early operative form of freemasonry, the latter being born in England around mid 17th century and reaching France circa 1725.

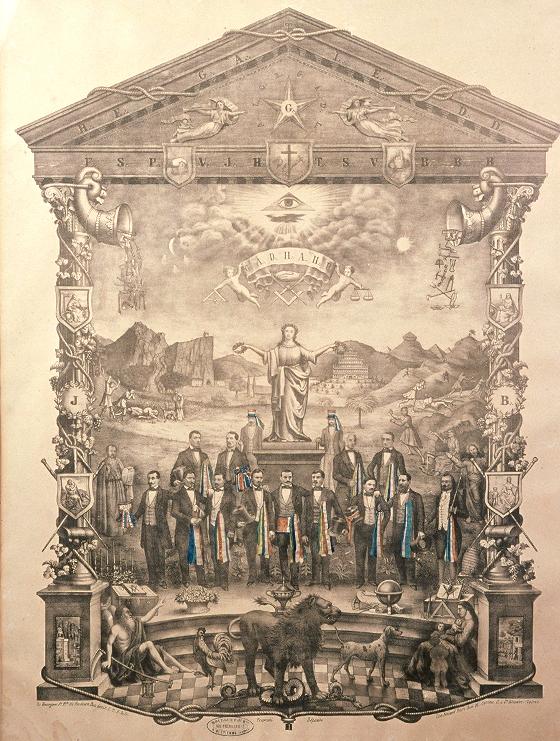

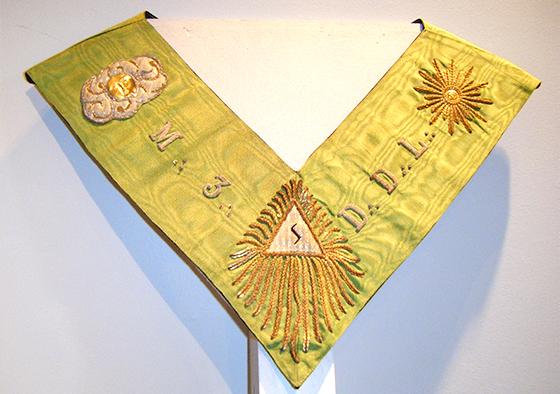

Conversely, attracted by the outlook of a prestigious society that appeared as a model with more meaningful esoteric contents, the compagnons largely borrowed from masonic symbols and rites to reform their own as early as the late 18th century. To this day, the earliest known example of such borrowing shows in a document of the Avignon stonemasons du Devoir dated 1782. During the 19th century these borrowings multiplied for several reasons. Firstly, there was a will after the Revolution to modernise an institution deemed ‘passé’ by the youth of the technically advancing new century. The second reason was that in that period an increasing number of compagnons became sedentary yet remained active parts of their brotherhoods; some of them had joined freemasons’ lodges and the influence of the latter was facilitated. Thirdly, the general level of instruction improved and more compagnons could read about freemason rites in the many books then published on the subject and felt they could enrich their own by borrowing elements from them. The best known examples are the legend of Hiram, the radiating star, the letter G, the three dots in triangular position and various symbols of the higher degrees. Combined with, or replacing, traditional elements of the compagnons’ rites with some adaptation, they were perceived as a new form of language by the 19th century compagnons.

Lithograph, “The Union of Building Trades”, circa 1875, featuring a number of symbols of Masonic origin

Chain of the 3rd order of Companion carpenters du Devoir de Liberté, circa 1850

German Companions in 1953

Great vase of the earthenware makers and potters society of Tours, circa 1848, detail

Masonic apron