Rites and symbols

From time immemorial, all human societies have had their rites and symbols; they are constituent parts of civilisations: funerary rites, religious rites, military rites, judicial oaths, matrimonial rites, greeting rites, etc. Symbols are just as numerous. Both are perceived as self-evident by a vast majority. Like any other initiation society, the Compagnonnage has its own rites and symbols but, as these are less publicised and are enacted by a restricted number of people, they arouse curiosity.

From time immemorial, all human societies have had their rites and symbols; they are constituant parts of civilisations: funerary rites, religious rites, military rites, judicial oaths, matrimonial rites, greeting rites, etc. Symbols are just as numerous. Both are perceived as self-evident by a vast majority. Like any other initiation society, the Compagnonnage has its own rites and symbols but, as these are less publicised and are enacted by a restricted number of people, they arouse curiosity.

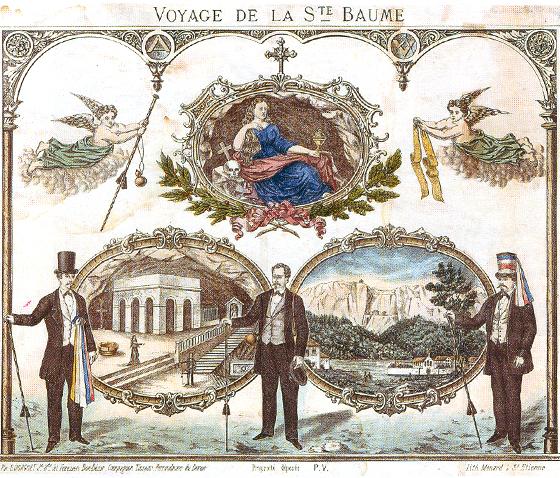

Some rites are still performed in open view: the ‘conduite’ ─ the leave-taking ─ when the compagnons in procession send the departing member on his way; the ‘guilbrette’ ─ the greeting ritual ─ when two compagnons drink with their arms interlocked; the ‘chaîne d’alliance’ ─ uniting chain ─ when compagnons join hands in a circle with arms crossed to close the patron saint’s day celebrations or at a funeral. Others are only used in the privacy of formal compagnons’ meetings: the introduction of a newcomer in a local branch, the reception of new compagnons, etc. The pilgrimage to the mountain of Sainte-Beaume in Provence is considered as a stage on a spiritual journey by the compagnons du Devoir.

In every case, their function is to transmit a code of morality, to affirm the bonds within the group, to educate, to confer dignity, to raise the young worker above his daily condition. The strict execution of a rite calls for self-control, which, amongst a group of exuberant young lads, was a quality worth cultivating for future integration in society.

Just as rites are a language made of gestures, symbols are one made of images.

A symbol raises questions, spurs the imagination and curiosity more than spoken or written words. A compilation of the symbols used by the compagnons would be fairly extensive, keeping in mind that they have evolved with time and within each craft. Some are taken from colours: red for courage, white for light or purity.

Tools have of course pride of place among them: the compasses stand for the domain of thoughts, reasoning, spiritual elevation and sound judgement ; set square symbolises rectitude, obedience to the rule, the concrete world; a level brings to mind equality, whilst scales represent justice.

Some are borrowed from Roman and Greek antiquity and from the Bible: the labyrinth suggests the arduous progress of the candidate towards reception, the Tower of Babel the doomed fate of a course motivated by arrogance.

Each craft brotherhood claims to have been founded by one of the three legendary figures of Father Soubise, King Solomon (with allusions to his architect Hiram) and Maître Jacques, but in fact, there is no trace of these myths of origin before the 18th century. They were meant to give the feeling that the Devoirs issued from an illustrious past, often linked to the building of Solomon’s temple.

The “Accolade” ceremony among the Companion Locksmiths of Tours (1852)

Journey from Sainte-Baume, lithograph, circa 1875

Symbolic painting of the Companion Dyers of Nantes, circa 1850

The labyrinth and the Tower of Babel on the colours of the Companions du Devoir

Pastille on a stick belonging to a Companion Wheelwright du Devoir

Bust of King Solomon, by Brabançon le Disciple des Arts, Companion Sculptor des Devoirs unis (1994)