Guild artefacts

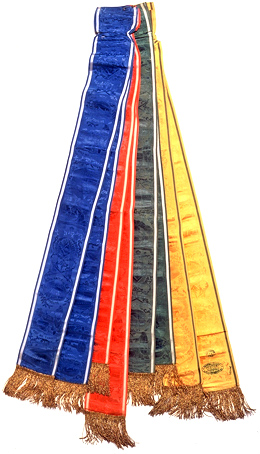

Objects are another point to be considered. On the day of his initiation, a guild member was given one or more silk ribbons, known as “colours”. Certain of the older colours are the simplest (a band of white, blue, red, green or some other coloured silk), 6 to 10 centimetres in width by 1 metre to 1.50 metres in length, generally without ornament but sometimes with initials embroidered at the tip. These are extremely rare, as few people down through the generations saw them as the most sacred attribute a guild had to offer. Others, such as those of the Stonecutters’ Guild, were decorated with woven flowers and resembled braided ribbons or curtain loops. These, too, are rare, for they were often mistaken for worthless pieces of old fabric. Other colours, less rare, were embossed between two heated rolls and reproduced scenes relating to the legend of Saint Mary Magdalene at Saint-Baume in Provence. Still others, worn as scarves, were of watered fabric embroidered in gold or silver thread with various symbols. Care should be taken to avoid possible confusion, however: photographs and prints of conscripts throughout the 19th century and into the period between the two Wars show them wearing hats with ribbons and often carrying large canes.

One sometimes comes across canes. These are never rustic affairs, made of wood and ornamented with a serpent or stems of ivy – such canes are not of the sort carried by guild members, even if a member may have made one for use on his travels. A true guild cane, of which there are no known examples before the beginning of the 19th century, was made of exotic, flexible bulrush. It measured 1 to 1.40 metres and had a brass ferrule surmounted by a steel ball. Two holes were drilled into it to allow for the passage of a thin, silk rope with two end-tassels or pompoms. The knob was either spherical or crooked, depending on era and guild. Canes were very simple until the mid-19th century when they began to be made of ivory and engraved with guild members’ nicknames, dates and places of initiation, and various symbols, their horn pommels adorned with an alloy or bone disc engraved with the same information.

Families may also have kept gourds (made of earthenware, coconut or calabash) and engraved with guild emblems and the owner’s name. Other small items have often been handed down from generation to generation, such as snuffboxes, patronymic plates, jewellery (signet rings, or gold earrings – known as “joints” – sometimes ornamented with small tools), or caskets. Some may occasionally be ornamented with guild symbols (an interlaced compass and square, or the initials of a member’s nickname). It would be well to remember, however, that a beautifully-decorated tool is not necessarily the work of a guild member; many non-guild workers also had their initials or some distinctive emblem (a heart, a star, or a fleur-de-lys perhaps) engraved on to their tools, thus making this particular method of identifying a guild member anything but foolproof.

Finally, there are the masterpieces. Here, one once again enters into uncertain territory. The first thing to remember is that the creation of a model certifying the professional competence of an “Aspirant” wishing to become a “Companion” was not a systematic formality. It was simply one of several ways of determining whether or not he had attained a certain level of competence. Until the mid-19th century, and even later, a considerable number of guild members were not called upon to make masterpieces. They were judged by their overall performance, usually in the workshop where they were employed. If a masterpiece was involved, it only concerned certain trades since others were ill-suited to their creation. One might find them among joiners (staircases, small arches, or doors), carpenters (roof trussing), wheelwrights (small wheels with multiple spokes), harness-makers (small collars), locksmiths (small pieces in wrought-iron), stonecutters (a design accompanied by a plaster model) and in a range of other trades. They were not, however, found among tanners, tawers, textile-workers, bakers, etc.

In addition, it was not unusual for workers in such trades as construction framing or joinery to create models without ever having travelled or joined a guild. Creation of reduced-scale models was common in the metalworking trades, in arts and crafts schools, in technical-training schools and on the railways.

It is a waste of time trying to locate the whereabouts of a masterpiece created by an ancestor who has been identified as a guild member. Apart from the fact that he may never have made one, there is also the unfortunate possibility that any masterpiece he actually had made has been destroyed. Until the 1950s, guild members kept the works they had made for their initiations, rather than giving them to the guild association to which they belonged, which is the procedure today. If one fails to find the masterpiece of a father or grandfather who was supposed to have been a “Companion” before this period it means that it has either disappeared, that it never existed, or that its maker was never a guild member. There is also little use in searching for it at the Musée du Compagnonnage in Tours, where only a tiny percentage of the many masterpieces created over the centuries are on display. That doesn’t mean, of course, that one should not go and admire those that are to be found there!