The reception

An initiation society, as defined by ethnologists, is a society that recruits its members through stages marked by secret rites. It sets a sharp distinction between the status of profane and initiated; the passage from the former to the latter is performed during a ceremony called initiation, or more to the point among compagnons: reception.

The rites and contents of the assay are always secret. The newly introduced member takes an oath never to divulge them. He is then acknowledged by the other members and is given the words and signs that will be used to prove his status when tested. The initiation can only be attended by initiated members.

All this may seem quite mysterious. In fact, the reception ceremony is experienced with simplicity and respect by the compagnons. The reception had, and still has, a triple aim. For one, it consecrates the acknowledgement of the other compagnons for the new one’s professional and moral achievements. In the past it was a way of offering to the most deserving a better chance of social and moral promotion, and of excluding those who wished to benefit from the advantages of the association while being unworthy of them. Secondly, the rites and symbols of the reception are the tools of a moral lesson aimed at imprinting the memory of the recipient with his duties unto the compagnons, the society in general and himself, and encouraging him to persevere on a rightful path. Lastly, the reception, through its psychological impact, strengthens the bonds among a group with common values.

Because he is supposed to have evolved from the state of aspirant to the one of compagnon, the newly received is given a compagnon’s name symbolising his rebirth. Compagnons’ names are built on patterns varying according to the rites and the craft brotherhoods, but the most usual form consists of a reference to the region of origin followed by a vertu, as in Bordelais la Persévérance. The joiners and locksmiths du Devoir differ in their own way as the reference to their place of origin is adjoined to their original first name, eg : Jean le Tourangeau. Among stonemasons and plasterers the vertu comes first, followed by the locality of birth, as in La Fidélité de St-Martin-le-Beau.

There are two, or sometimes three, levels of membership in a craft brotherhood. For the first, ‘aspirant’ is the word most commonly used, but there is also ‘affilié’ in the Devoir de Liberté and ‘jeune homme’ among the stonemasons des Devoirs. Since the 1950s, it is bestowed in a ceremony where skill and moral behaviour are assessed. The second, that of compagnon, is accessed during the more elaborate reception for which a masterpiece must be produced. Some brotherhoods also have a third level called ‘compagnon fini’.

In spite of the secrecy sealing the reception, a number of ancient descriptions of their contents are known to us, either from the 17th and 18th centuries as results of inquiries instigated by the Catholic Church, or from revelations in the 19th century from disgruntled members, or from manuscripts held in the public archives. It appears that the contents of these ceremonies is quite different between craft brotherhoods and also that they changed with the passing of time.

The earliest known reception ceremonies are based on the Christian lore : as in the mystery plays of the Middle Ages, the candidate relived some moments of the life and passion of Christ. During the 19th century the trend is for the rites to drift away from their Christ-like aspects and to integrate borrowings from freemasonry. They still continued to adapt after the 1950s to conform with the cultural, religious and psychological evolution of present-day young people.

All reception rites comprise episodes aiming at testing the sincerity, will, courage, moral behaviour and commitment of the candidate. The oath to be faithful to the Devoir and its followers is a crucial element of them.

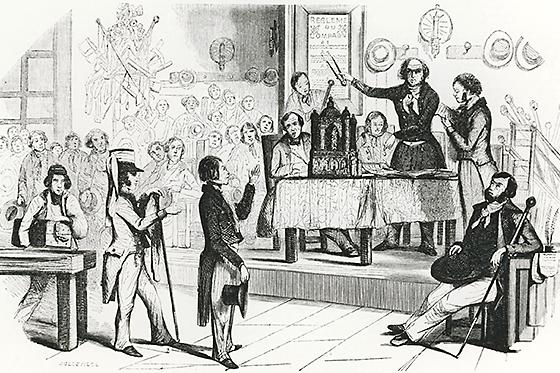

The reception ceremony, according the newspaper “L’Illustration” in 1845

Knob of a Companion Baker du Devoir’s stick

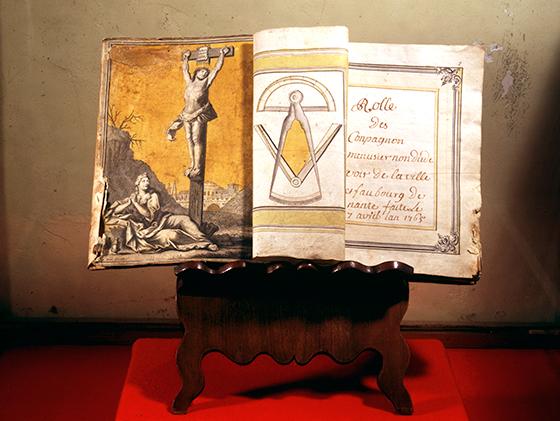

Roll of the Companion Carpenters non du Devoir of Nantes, 1765

The oath, detail from a lithograph of the Companion Cloth-makers, circa 1850