19th century

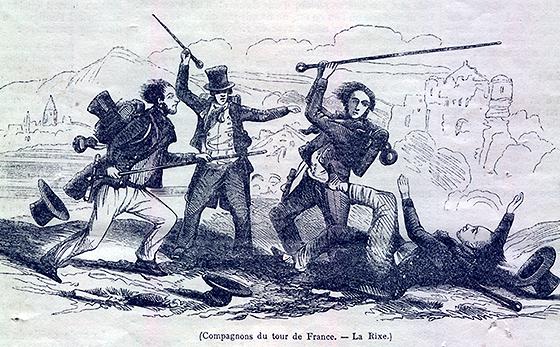

Under the Empire (till 1815) the craft brotherhoods were still forbidden, but, unable to erase them, the authorities could at least keep an eye on them and prevent strikes and shop-banning. Brawls were rife again. Later, the Compagnonnage was confronted with the expansion of industry, the decline of its memberships and was brought to consider regrouping to survive.

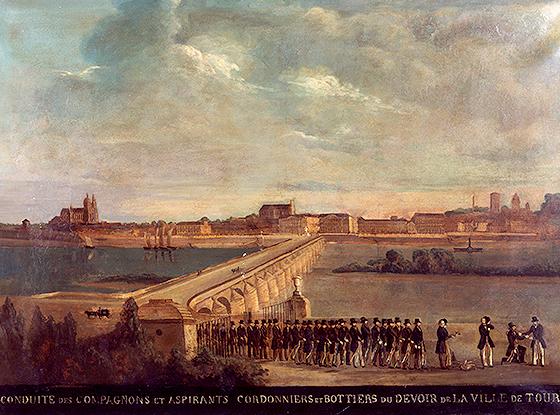

At the beginning of the century, the compagnons’ brotherhoods appeared as the only organisations defending labour rights, and several crafts emulated their model. Such was the case for shoemakers (1808), clog-makers (1809) and bakers (1811) but they were rejected by the other compagnons du Devoir. New divisions appeared inside the Devoir among bakers, shoemakers, carpenters and coopers. The dissidents took sides with the Devoir de Liberté. These internal tensions and separations weakened the Compagnonnage, already having to face the industrial revolution. The introduction of machines severely cut down the need for skilled workers in many crafts, particularly in the textile department (dyers, cloth-shearers, linen-weavers, hatters) and also the tanners, chamois-bleachers, founders, knife-makers…

The Tour de France, disorganised during the Revolution, had fewer stopovers. Innovations made their way into the rites of most brotherhoods; many were copied from freemasonry which appealed to the compagnons with its prestige, its rites and its symbols.

During the second half of this century, the Compagnonnage was in decline. Many workers preferred to join other forms of association where they could find the same assistance minus ‘the mysteries’, the constraints and the quarrelsome bias: the mutual assistance societies and, after 1864, the ‘chambres syndicales’ inspired by the trade unions.

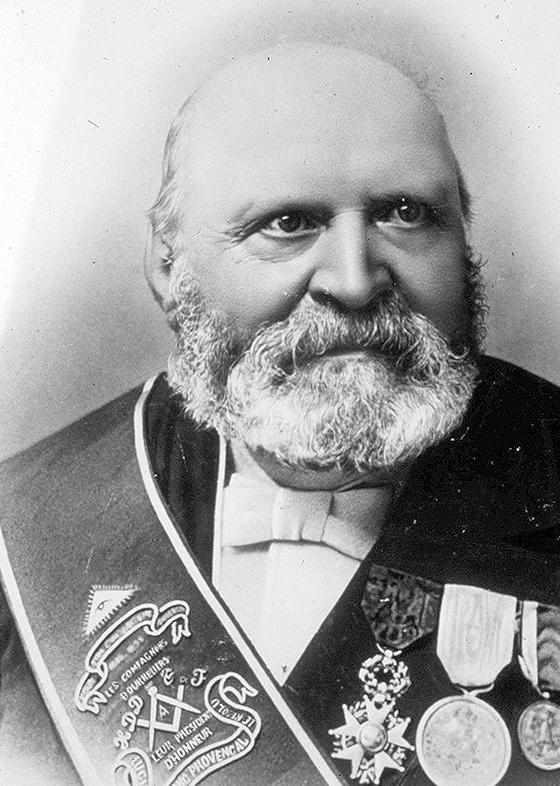

A few compagnons initiated a movement to put an end to the brutal rivalries inside the Compagnonnage, being conscious that these quarrels weakened it. The most famous of them was a joiner compagnon du Devoir de Liberté named Agricol Perdiguier, aka Avignonnais la Vertu (1805-1875). He published the ‘Livre du Compagnonnage’ in 1839, then his ‘Mémoires d’un compagnon’ in 1855. Thanks to him, and the other like-minded compagnons, violent brawls ceased almost completely after 1850.

Little by little, the craft brotherhoods of the compagnons, formerly composed exclusively of young men, came to rest on older, married and settled compagnons to run them. These elders animated parallel movements that bridged Devoir and Devoir de Liberté. Between 1860 and 1889 retired compagnons formed associations that federated without discrimination, organised congress and set up the Fédération de tous les Devoirs (later to become the Union Compagnonnique des Devoirs Unis that is still active today). The leader of this movement promoting progress through reform was Lucien Blanc, a harness-maker, aka Provençal le Résolu (1823-1909). This attempt at fusing all the craft brotherhoods in one structure did not completely reach its aim; quite a number of compagnons remained true to their original organisations.

In the last decades, being then a minority among skilled workers, the compagnons had lost leverage against the employers and it was then up to the unions to trigger off a strike.

A brawl, engraving from the review ‘L’Illustration’, 1845

Leave-taking celebration for the shoemaker compagnons of Tours in 1850

Agricol Perdiguier (1805-1875)

Lucien Blanc (1823-1909)