17th century

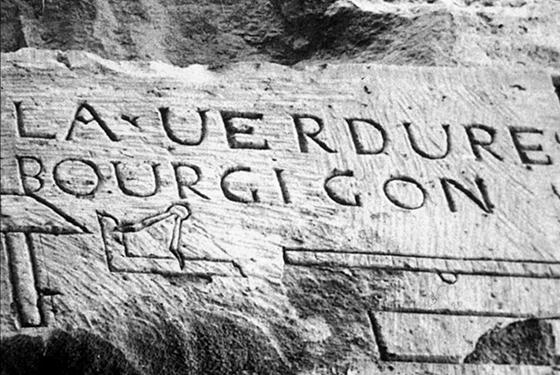

In the 17th century we learn of divisions between brotherhoods and problems with the Church. The documents concerning the compagnons increase noticeably and relate to numerous crafts. They reveal that the compagnons’ brotherhoods were based in many French towns. Stonemasons, imitated by others, left their names and symbols in graffiti on the Pont du Gard, a spiral staircase in the former cathedral of St-Gilles-du-Gard and Diana’s temple in Nîmes, etc.

Joiners were sued in Dijon for their scheming against employers and their brawls between rival brotherhoods. Throughout the century, compagnon societies are evidenced among stonemasons, carpenters, joiners, wood turners, hatters, shoemakers, saddlers, bonnet-makers, founders, locksmiths, farriers, tailors, knife-makers, printers.

From 1645 until the end of the century, the Church scorned and condemned the ‘impious, blasphemous and superstitious practices’ of several craft brotherhoods. In 1655 in the Sorbonne, it pronounced a writ against them at the instigation of Henry Buch, founder of the ultra-pious Shoemaker and Tailor Brothers.

The judiciary records show the existence of two rival associations of joiner compagnons in 1677 in Dijon: those of the Devoir on the one hand and the Gavots (or Gaveaux) on the other. Contrary to a largely publicised assertion, there is no evidence that their opposition had its roots in the conflict between Catholics and Protestants. The same situation could be found among hatters.

Stonemason’s graffiti, Nîmes.

Henry Buch